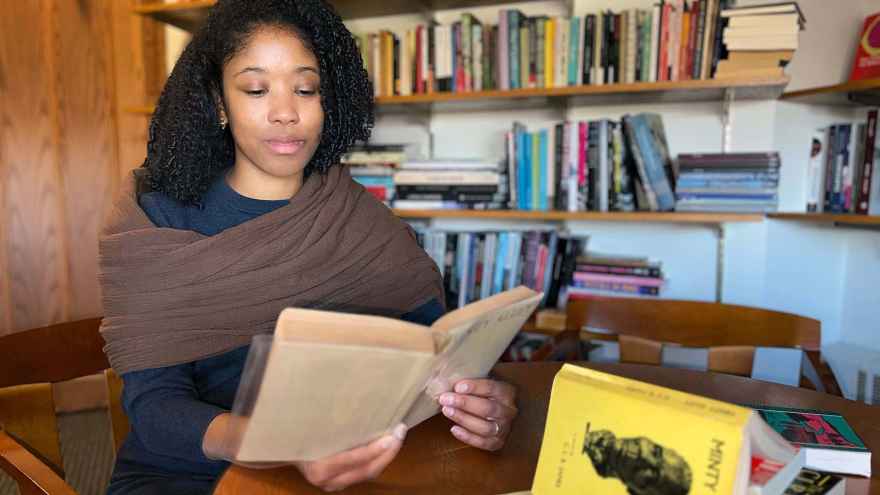

English faculty Kaneesha Parsard traces an alternative ending to Minty Alley by C.L.R. James

By Arts & Humanities news staff, with reporting by Misha McDaniel

October 28, 2025

C.L.R. James—historian, Marxist theorist, cricket commentator, and one of the twentieth century’s most prolific writers—wrote only one novel in his lifetime: Minty Alley (1936). Set in a Trinidadian yard, a form of communal housing, the book follows Haynes, a middle-class man navigating life among working-class neighbors.

Nearly ninety years later, Assistant Professor of English Kaneesha Parsard encountered a set of five new pages of Minty Alley—typed and annotated in James’s hand—that reimagine the novel’s ending.

In the published ending, the yard is sold and its residents dispersed. But in the five unpublished pages Parsard uncovered, the landlady Mrs. Rouse dies, leaving most of her property to Haynes. Instead of collective dispossession, the middle-class protagonist acquires wealth and stewardship. For Parsard, that pivot reframes Minty Alley not as a coming-of-age story, but a site where James worked through the shifting politics of class, independence, and sovereignty in the Caribbean.

“At first I thought I had misremembered the ending,” Parsard recalled. “But as I kept reading, I realized these were entirely new events—characters acting in ways I had never seen before!”

Parsard first visited the C.L.R. James collection at the University of the West Indies (UWI) in 2012 as a Yale doctoral student, before the materials were cataloged. Parsard relied on the guidance and expertise of library staff Lorraine Nero and Aisha Baptiste to sift through the papers. Years later, as a Provost’s Postdoctoral Fellow at UChicago, she returned to the archives in 2019. With the help of Nero and Baptiste—and their newly updated finding aids—she came across a folder containing the other ending.

For Parsard, that moment underscored the collective and often invisible labor that makes archival research possible: the meticulous work of cataloging, the knowledge of librarians, the fragility of underfunded collections. The archivists mended the gaps; the new cataloging system left materials poised for research. “Without that groundwork, I wouldn’t have found the ending,” Parsard said.

Dating the manuscript became its own detective story. The undated pages could have been written anytime between the late 1920s and the 1970s—when James first wrote the novel to its reissue by New Beacon Books in 1971. Parsard compared handwriting samples in collections at UWI and Columbia University, studied how James’s intermittent illness affected his penmanship, and even consulted the Society for the History of Authorship, Reading, and Publishing to analyze typewriter and ink. But still, it wasn’t enough to pinpoint a date.

A breakthrough came with a 1960 letter where James mentioned rewriting Minty Alley. That clue led Parsard to Selma James—C.L.R. James’s former wife and longtime Marxist feminist organizer—who was delivering a talk at the 2023 London Anarchist Bookfair. “I’m very shy in the audience, but I went up to her,” Parsard said. “She’s 93, she’s busy, still a full-time feminist organizer and yet generously made time to meet with me.” They talked about Selma’s memories of the novel and when James rewrote it. Together, they placed the pages in the 1960s, when James was breaking with Prime Minister Eric Williams and rethinking the future of the People’s National Movement.

“It was a period when James was asking: what does sovereignty look like? Who gets to determine the future—the political elite or the masses?” Parsard said. “The meaning of the alternative ending started to coalesce. The published version is collectivist. The revision experiments with placing stewardship in the hands of a single heir.”

For Parsard, the unprinted pages lay bare how James used fiction as a workshop for political thought. While he agitated and supported democratic experiments in the West Indies, he was also experimenting with ideas of his own—testing out models of power, inheritance, and independence through narrative form.

“An alternative ending to Minty Alley […] plays with the intimacy and distance among the West Indian writer, the middle class, and the working class,” Parsard wrote in a recent article. “It exemplifies James’s tendency to revise.”

The archive, then, is not a storehouse of drafts and dust but a living record. In Parsard’s hands, unfinished work unsettles the canon, reminding us that even a “finished” novel can still be in motion—and that literature itself is a laboratory for political futures.

You can read Minty Alley’s alternative ending, along with its historical context, in Parsard’s research article, “An Alternative Ending to Minty Alley.” Parsard can be reached at kparsard@uchicago.edu for a PDF.