News

MacArthur Foundation supports UChicago initiative to explore future of the humanities

Arts & Humanities Day 2025 sparks citywide conversation

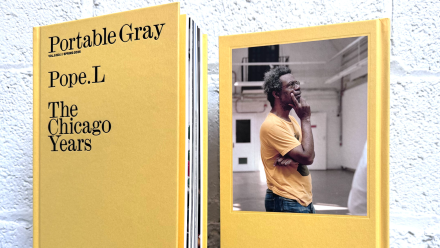

Theaster Gates redeems discarded materials in Smart Museum’s ‘Unto Thee’

PhD student Naomi Harris publishes three new Hittite poems in The Paris Review

Grossman Ensemble honored by Library of Congress invitation

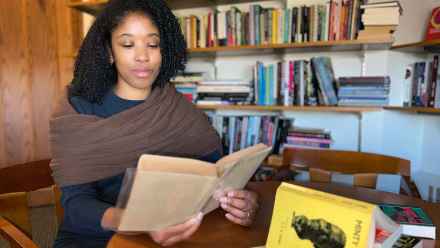

English faculty Kaneesha Parsard traces an alternative ending to Minty Alley by C.L.R. James

Josephine McDonagh, Professor of English, elected to the British Academy

Hexacago Health Academy marks ten years of game design education

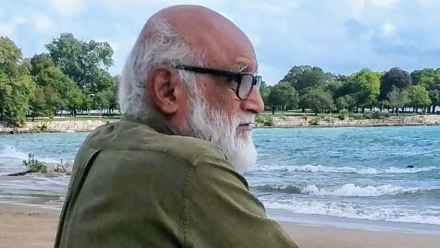

C.M. Naim, pioneer of Urdu studies and beloved mentor, 1936–2025

UChicago Arts & Humanities Day Announces Speakers, Partnership with Chicago Humanities

Building the Future of Arts & Humanities at UChicago: Responses to Frequently Asked Questions

Deborah Nelson, Dean of the Division of the Arts & Humanities and Helen B. and Frank L. Sulzberger Professor of English and the College

What is the scope of work in the arts and humanities at UChicago?

UChicago’s research and teaching in the arts and humanities is conducted at a scale and level of impact with very few peers. The Division of the Arts & Humanities is home to more than 200 tenure-track faculty members and 200 specialists in language teaching and many forms of arts practice—one of the largest arts and humanities faculties in the world. The division teaches 50 languages or more in any given year. In 2025, a third of all undergraduate degrees at UChicago included a major or minor in the arts and humanities.

How is UChicago’s Arts & Humanities Division planning for the future?

During the summer of 2025, more than 50 faculty and staff within the division began working to plan for the long-term vitality of the arts and humanities at UChicago. This faculty-led work has generated ideas to help us discuss ways to ensure our academic community can continue to produce the kinds of humanistic knowledge that is essential to engaging the pressing issues we face as a species, such as: How can cultural and historical insights inform how we navigate the impacts of climate change? How does our understanding of language shape artificial intelligence, and how does AI change understandings of language, truth and other concepts at the core of the humanities? And even first-order questions about how we live together in a pluralistic society with shared but limited resources, in a global milieu with increasingly fluid boundaries. These are questions our students want to pursue, too.

What is the status of the faculty-led planning work that began in summer 2025?

I have shared with all faculty and staff within the Division of the Arts & Humanities the reports produced by the faculty-led committees convened during the summer of 2025. The findings and recommendations of those reports have provided a starting point for ongoing discussions and long-term planning within the division and with university leadership.